On Friday, MinIO's community repository was effectively put on ice. The reporting and community threads around it are blunt: a project that many teams treated as "open source infrastructure" can still be steered, gated, or abandoned when one company holds the keys.

When I initially started writing this blog post, I'd just seen a post in which Peter Zaitsev answered the same question for MySQL at the Belgium FOSDOM conference.

I wanted to answer this question for Postgres, but while I was writing, Friday the 13th happened. While neither Pamela nor Jason came around, MinIO decided to finally cut ties with its open-source heritage.

And I decided to start over, with a different view at the question "who owns Postgres," and what does the answer mean for us in a world where one of the most-starred GitHub projects was just "abandoned."

No One Owns Postgres

If you've spent any time in database land, you've heard the line: "No one owns Postgres." It gets tossed around in slide decks, vendor talks, and comment threads like it's a vibe, not a fact.

However, it's the truth, and that's not marketing fluff. It's the structural reason PostgreSQL keeps winning in places where "trust me, bro" roadmaps and license drama get people fired.

An "open source" project that's effectively owned by a single company is strategically dangerous.

Postgres is resilient precisely because it is not owned that way. And it's also why Vela uses vanilla Postgres and aims to upstream changes: if you care about long-term safety, you don't want your core data layer to depend on a vendor's willingness to keep the "community" path alive.

Ownership Is a Lever, Not a Vibe (the MinIO Lesson)

When people say "open source," they often mean "I can docker pull it, and it works." But governance is where the real power sits, and some companies take the open-source train to increase usership before slowly pulling the plug.

MinIO is the cautionary example because the failure mode is so familiar:

- First, you adopt a "community" version.

- You build assumptions into your ops, applications, and tooling.

- Then incentives shift (like investor pressure), and they change packaging, move features, complicate contribution flow, or deprecate and unmaintain repositories.

In February 2026, MinIO's repo status change to "no longer maintained" (and related actions around the repo) became the new headline. Whether you see it as a reasonable business move or a trust breach, the risk for users is the same: one company can unilaterally change the rules of the game.

That's what "company-backed open source" means in practice. While you have access to the source code, there is an asymmetrical shift of power. And while a small group already forked MinIO, the first step toward killing MinIO open-source happened all the way back in 2021, when MinIO relicensed from the Apache License 2.0 to AGPL. A move that has complicated its use in commercial products ever since. It was the first move towards pushing people out of open-source and into paying customers.

The Meaning of "Owning" in Open-Source

As we learned, with open-source projects, owning isn't always the same as owning.

When a team says "company X owns project Y," they commonly refer to one or more of the following owning schemes:

- Copyright control determines who owns the copyright to the actual source code. It basically regulates who is able to relicense the codebase, and many large companies centralize this authority by requiring you to sign a CLA (Contributor's License Agreement), with you signing off on your right to veto.

- Trademark control defines who controls the name and branding. Some companies are very open about this control, while others tightly restrict who can use it and how. I'm looking at you, Oracle.

- With roadmap control, owners of an open-source project directly steer the future direction. They decide what gets built, how it is prioritized, or what features might be "moved to enterprise versions."

- Distribution control means who ships "the official" binaries, containers, repos, and upgrades. Who manages vulnerabilities, and when and how security patches are released.

- Lastly, governance control defines who can merge, who can block, and who sets policies.

For a pure open-source project, like Postgres, the answer to all of the above should be "the community."

With open-source projects that run as company-backed or company-sponsored, the answer to one or more of these questions would be "company X."

While plenty of company-backed projects run fine with a strong corporate steward, they only do so until they don't. The moment revenue pressure, competitive pressure, or acquisition pressure shows up, those levers start moving. And MinIO is far from the only example. Another recent example of an attempted "un-open-source" move was Synadia.

The good thing, "no one owns PostgreSQL," isn't just a philosophy. It's a promise. It's risk reduction by design.

Luckily Postgres Can't Be "Captured" Like Vendor-Owned Projects

PostgreSQL loves to be boring. Not in the sense of being limited in features or slow, but in the way it is meant to be developed. Its internal processes are intentionally designed to prevent a single party from taking over and steering its direction.

- A long-lived review cycle with extensive discussions on its mailing lists, and the requirement that a good chunk of the community needs to agree.

- The merge rights held by individuals (internally known as committers) who act as stewards. Getting a feature into Postgres without the support of at least one committer is impossible.

- And finally, no single corporate entity that can flip the table and relicense the whole thing. The governing body is the PostgreSQL Global Development Group.

This is also why Postgres doesn't have the same "surprise relicensing" risk profile as projects where a single copyright holder can decide the future on a Friday. PostgreSQL's development can seem old-fashioned and sturdy at times, but it prevents us from such risks.

Compare that with ecosystems where ownership is explicit and centralized, such as MySQL (Oracle-owned) or MongoDB's SSPL shift, which are classic examples of how incentives can rapidly change rules.

The key point: Postgres is a project, not a product with a commercial owner. There are many vendors that built huge businesses around Postgres, but they don't get to say what Postgres is.

Open Core: "Open Source Cosplay" - Licenses Still Matter

Jeffrey Paul put it sharply:

"Open core is not open source, regardless of what license they use. It's what I've taken to calling 'open source cosplay.'"

While I don't fully agree with the "open core is always bad" framing, I think we did a good job at Hazelcast (at least at the time I was around). It is difficult to remain true to the open-source way of thinking in business. At the time, we removed one feature from the open-source version and moved it to our enterprise bundle.

Today, as at the time, I thought it was a huge mistake. It came in response to pressure to include one more feature that people were willing to pay for. However, we did everything possible to ensure others were able to bring it back with minimal work. The feature was TLS encryption, and customers wanted a certified version. We never went back to make the same mistake again.

I strongly believe open core can be done right if the company genuinely preserves user freedom, avoids bait-and-switch dynamics, and doesn't try to trap the ecosystem. Having been there myself, I know how hard it is to maintain this line of thinking under pressure.

Anyhow, the quote is compelling because it identifies a real pattern: many companies market themselves as "open source" to facilitate rapid adoption, growth, and credibility while using governance, licensing, and packaging to maintain asymmetric power.

That's also why permissive licenses like the PostgreSQL license, the Apache License 2.0, and the MIT license matter. They don't guarantee good behavior, but they make it harder to build a moat out of licensing and easier for ecosystems to remain forkable and competitive.

If a company moves away from permissive licensing or starts tightening distribution and contribution in ways that reduce symmetry, take it with a grain of salt. Not because the software is suddenly bad, but because the risk profile just changed.

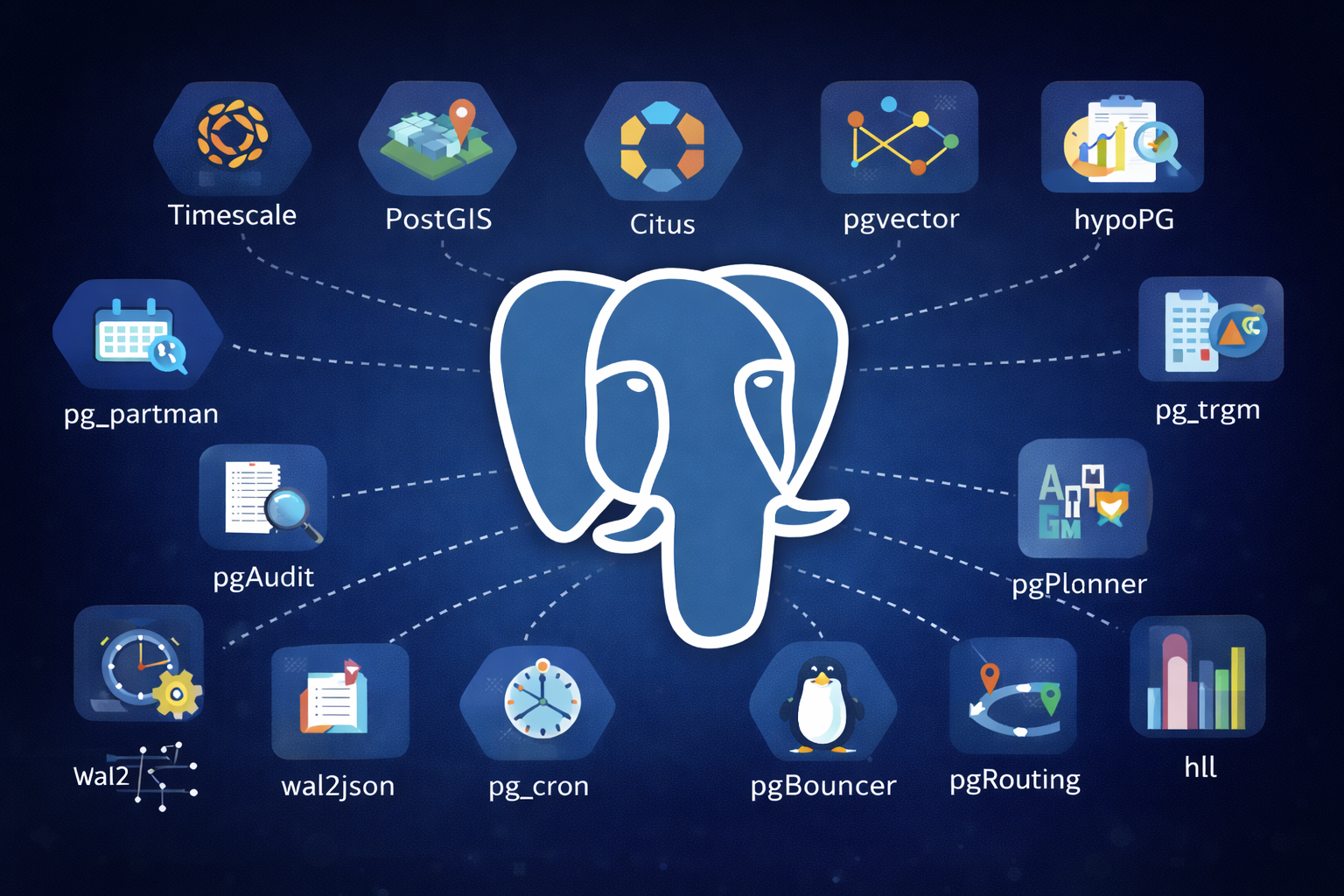

Innovation Without Fragmentation: Extensions, Tooling, and Upstream Discipline

With successful open-source projects, we commonly see a vast ecosystem flourish alongside the core project. With company-backed projects, it's often unlikely to see other commercial offerings. In particular, since MongoDB, more and more companies have adopted a dual-licensing strategy in which the "open-source license" imposes significant constraints on potential endeavors.

On the other hand, successful community-driven open-source projects such as PostgreSQL enjoy a rich ecosystem with multiple companies providing commercial support, hardened and certified versions, or bundling additional customer benefits and features.

However, a healthy ecosystem needs commercial incentives and safety rails. That's why Postgres provides a feature-rich SPI to extend functionality and behavior. Most differentiation between Postgres from company A and Postgres from company B lives in:

- managed hosting and SRE excellence,

- backup, disaster recovery, observability, compliance workflows,

- performance engineering and deployment automation,

- operators, integrations, and platform ergonomics,

- and extensions (data types, indexes, FDWs, background workers, etc.).

This is the "pressure-release valve" that keeps Postgres evolving without turning into "Postgres, but..." forks that slowly drift into a different database.

When we announced Vela, I said forking shouldn't be taken lightly. And I really believe in this. Forking is easy, but maintaining a fork is brutal. The minute you diverge meaningfully, you inherit every upstream fix, every subtle correctness edge case, and every release engineering headache forever.

So the most sustainable pattern is: extend where it's safe, and upstream what should be shared.

Platform Team Checklist: How to Spot Single-Company Risk

The recent move from MinIO is just one step in a long walk of "open-source companies." That means it's important to understand the potential risk of every product and infrastructure component in your stack.

Therefore, here are the signals to test if an "open source" project may still be strategically owned by a single company and carry a potential risk of being relicensed or abandoned:

- Single-vendor copyright aggregation (CLAs that centralize rights or dual-license setups).

- Company-owned trademarks are used to restrict and police competing distributions.

- "Open-source" steadily loses important features that are migrated to enterprise versions.

- Distribution chokepoints guard the publishing of official binaries and images. When vulnerabilities are fixed late in the open-source lifecycle, images and binaries disappear, and licensing gates appear; be careful. "Source-only" is not open-source.

- With governance opacity, decisions are made in private, and community input is largely symbolic.

- Repo status drift ends up with "maintenance mode," "archived," or "unmaintained" repositories.

None of these automatically mean "never use it." They mean that you must price in the exit cost and avoid building a platform where your only move is "hope the vendor stays nice."

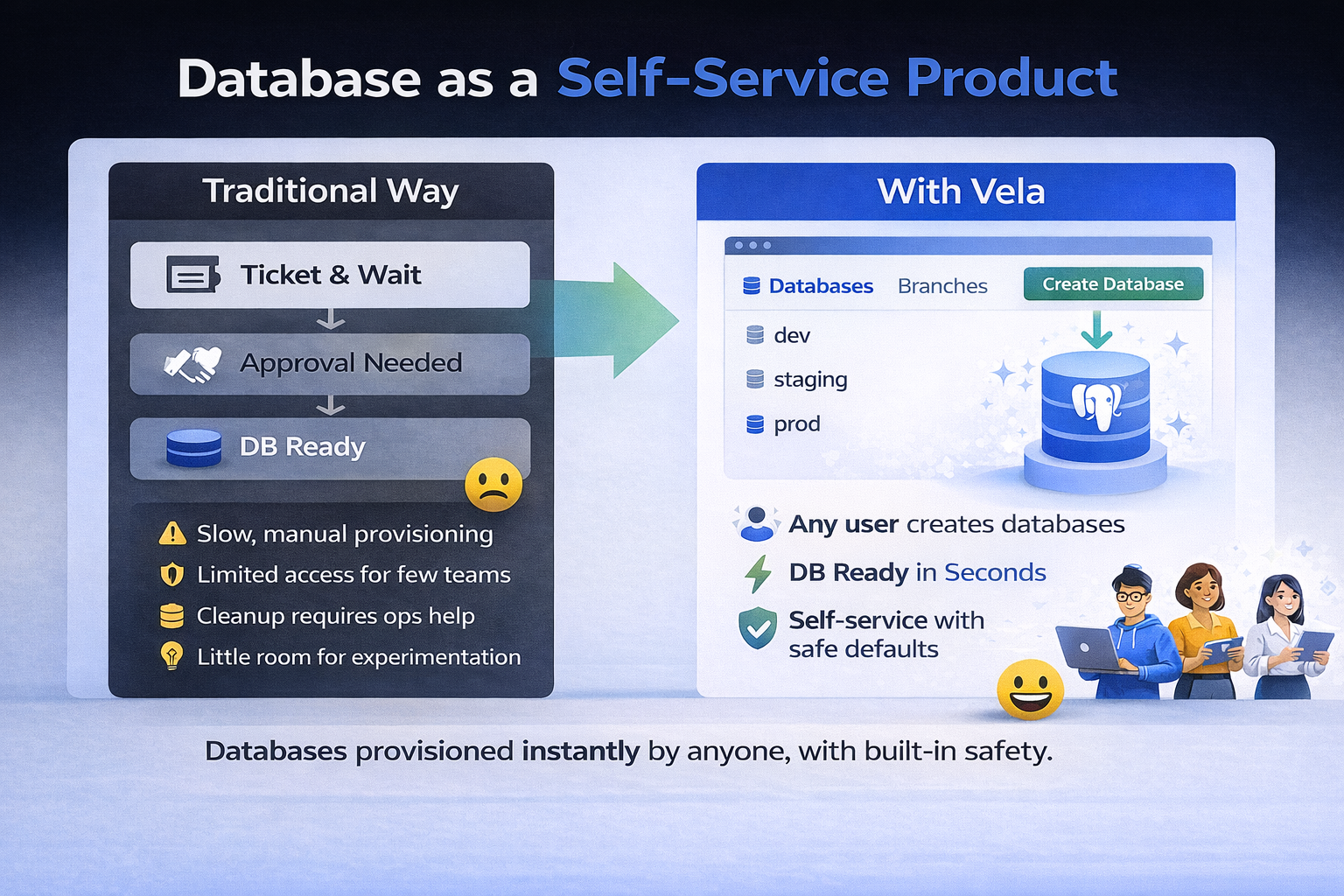

Vela Sticks to Vanilla Postgres

When we decided to build Vela, one decision was clear before anyone brought it up: Postgres.

PostgreSQL is the choice of database. From an open-source perspective, from a feature-richness perspective, from a speed perspective, and from an ecosystem perspective.

Vela uses vanilla Postgres as its database foundation. Both in the system-orchestration layers and in the user-facing databases. Our focus is to change the experience of how you consume Postgres, how you create and maintain your database schema, and how you write applications using Postgres.

That said, we sought to present users with the power of Postgres itself, not something that may look like Postgres from the outside but isn't merely a drop-in replacement. Many alternatives that "speak" Postgres differ in how queries are run. Don't just drop your code into any of them and expect all your queries to perform as they do on PG.

Anyhow, Vela will have differentiators, either as extensions or if in the core, upstreamed to the PostgreSQL project. We strongly believe in the principle of symmetric power balance and the concept of open-source over licensing roulette.

If you want to learn more about Vela, see our open-source announcement blog post and learn why we decided to fork Supabase. If you test it out, let me know what you think. We aim to develop Vela together with the community. Together with you.

To close, the MinIO situation is a timely reminder that source availability isn't the same as shared control. Postgres' model is durable precisely because no single company can pull the rug in the same way.

Nobody owns Postgres.

Everybody owns Postgres.